Sermons 2025

Trinity XVII, Harvest Festival Sunday 12th October by Fr Jack

With the Worshipful Company of Gardeners

Jeremiah 29. 4-7

2 Timothy 2. 8-15

St Luke 17.11-19

It is a great delight to have our friends the Gardeners’ Company back with us for Harvest. Master, Wardens, members of The Company, your presence here adds so much to our keeping of Harvest, which let’s face it, is a rather strange enterprise here in The City. The markets here do sell fruit and veg, but as digits on a screen representing global markets, more than streets full of fluffy cauliflowers piled up in wheelbarrows.

But, ‘No!’ I hear you cry.

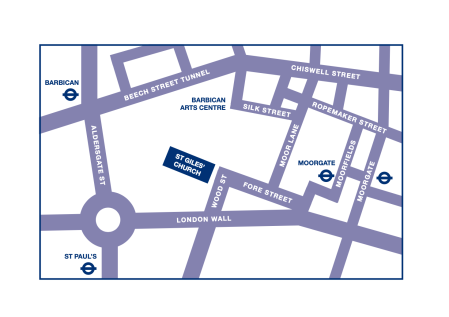

What about St Giles’ Urban Farm. We are thrilled to be partnering with our friends at The City of London School for Girls and other neighbours here in the parish to green the churchyard out there with the growing of vegetables. Do get involved if you’d like. The Master Gardener, also a City Alderman, is the Chair of the Girls’ School. It is a lovely project of people coming together to make a difference locally.

A good reason, then, to keep Harvest here at St Giles’.

And we’re the parish of Mark Catesby, the famous naturalist. And we’re the home of the annual Thomas Fairchild Service, Fairchild the leading nurseryman of his day.

So having established all that, it is the task of the preacher to shoehorn in some stuff about Jesus that is tangentially connected to horticulture or agriculture.

‘Not so!’. This time its me crying out, even if you’re not.

Because Harvest is not Gospel-related-but-adjacent. No, Harvest reflects some of the most fundamental Gospel truths.

The Harvest-time Gospel is one that flows all the way from Eden to Jesus’ healing ministry. God invites us to steward the Earth and everything in it with love; gently, generously and well.

In today’s Gospel the man with leprosy comes back to thank Jesus: harvest is a feast of gratitude, of cultivating a lifestyle of gratitude and generosity.

St Giles’ has recently helped partner one of the local independent Preparatory Schools, Lyceum, with our own St Luke’s Church of England Primary School for Harvest. The harvest offerings between the schools were wonderful. The children show us the way: in the current climate of estrangement and insecurity, the harvest is a time of embracing our identity as God’s children in one human family, a spirit of communion and openness.

All these are fundamentals of Jesus’ ministry - giving to the poor, thanking God, allowing no one to become ‘othered’ or ‘outside’ our concern. They are fundamentals for Jesus, and for Harvest. Let’s turn to the readings set for today and see what emerges.

We are invited by the Gospel given for today, and the Good News of Jesus as a whole, and the message at the heart of harvest, to make thanksgiving the pattern of our lives. It sounds a small thing to do. It is not.

As we’ve already said, all the people with leprosy were cleansed, but only one shows the theological excellence of coming back to say thank you. Gratitude is what marks him out as wise and right.

We here aspire to the same virtue of gratitude. It is at the heart of Christian life all year round, not just the Harvest. Each day we are invited to begin and end in prayer; and a prayer of thanksgiving is often the most honest and best prayer we can offer. For life itself, no matter the challenges we face, which we also bring to God in prayer. For the people in our lives - those we rush to thanks God for, and those we don’t!

But more than that, we choose to be here. The Eucharist/Holy Communion/The Mass/The Lord’s Supper is the source and summit of Christian life. It is the ground beneath our feet, our food for the journey, and the destination towards which we live. It is the drumbeat of our lives Sunday by Sunday and day by day. And at its simplest, it is what it says on the tin: Eucharist - that is of course, thanksgiving in Greek.

We are people who day by day, Sunday by Sunday, harvest by harvest choose to define our lives by thanksgiving. It sounds so simple and inoffensive, but it is in fact radical and remarkable.

I, we, make our life an act of thanksgiving by being part of the Eucharist every Sunday, and midweek. We choose this pattern and character for our lives. And everything else in our lives flows from this thanksgiving we have chosen: our politics, business, family, community. By being here, and then by living from here (or at least trying to!) - by living out the themes of Scripture, living out the texture of hymnody and sacred music, by living lives that resound with the love of the One we have eaten and drunk here. Transformation by thanksgiving.

For some that might be how we live with responsibility at home, work or elsewhere. How we live with the effects of ageing or complex health. For some it might be how we consider vocation, what our lives are for and what they will be.

And how we live is what Jeremiah wants us to attend to today.

Build, plant, garden, eat, says the Prophet Jeremiah. Seek the welfare of your surroundings and be a blessing to them, as you receive the blessings of them. A wonderful philosophy at the heart of the Harvest, so appropriate for gardeners here today, and at the heart of Christian life.

Seek the welfare of your surroundings and be a blessing to them, as you receive the blessings of them. Realise that we are all inextricably part of a greater whole; and live with gratitude, as a blessing, says Jeremiah to us today. As we hear these ancient words, how does that affect the way we care for the world that God has entrusted to us, how we formulate our politics and identity in a climate so eager to estrange us from one another, and grow fear and propagate insecurity? Jeremiah has a lot to say to us today, and we would do well to listen deeply.

And one of the things that will help us to listen deeply and live well is what St Paul is getting at today in his letter to St Timothy, today’s epistle, with which I’ll finish. The Apostle Paul wants us to see that it’s all a matter of perspective. The death and resurrection of Jesus changes everything about how we are invited to see life. Value, purpose, what really matters - it is all fundamentally changed by living in the light of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. And (and I’m not being silly here) it is not so unlike the perspective of a gardener. The gardener requires a perspective informed by trust, patience, by a rejection of cheap profits or flash-in-the-pan quick results. We do rejoice in the simple and immediate beauty of a bloom, but it doesn’t stop us having the hope-filled long-term perspective of nurturing and nourishing growth over years and years sometimes, before results start to show. The gardener cannot exploit and walk away, the gardener persists in loving care-ful relationship. There is something of this spirit in St Paul’s words today.

So the Harvest is not such a strange thing in The City after all… You see how it all comes together? The perspective on life that St Paul and Jeremiah are inviting us to embrace. And perhaps the key to it all: how gratitude is not a nicety, but a radical and truthful way of really living - a Eucharistic life.

Trinity XVI, Sunday 5th October

A sermon preached at The Charterhouse by the Rev’d Lucy Newman Cleeve

Habakkuk 1:1–4; 2:1–4

Luke 17:5–10

“How long, O LORD? Must I call for help, but you do not listen? Or cry out to you, ‘Violence!’ but you do not save?”

These opening words of the prophet Habakkuk were written 2,600 years ago. But they could have been spoken this week in Manchester, where worshippers gathering on Yom Kippur were attacked at their synagogue. Three dead. “How long, O LORD?”

The question echoes from Ukraine, where hundreds of thousands have died since Russia’s invasion. From Sudan, now the world’s largest humanitarian crisis. From Gaza and Israel. From Myanmar’s civil war. From Syria, from Yemen. How long must violence prevail? How long must the wicked surround the righteous?

But we might also hear them closer to home, in our own nation’s divisions, in the weariness of those who see injustice persist and public life corrode through cynicism or greed. “How long, O LORD?”

These are the questions Habakkuk asked about his own broken world. And what makes Habakkuk distinctive among the prophetic books is its structure. While prophets like Jeremiah included complaints to God alongside proclamations to Israel, Habakkuk is largely framed as dialogue between the prophet and God, ending not with proclamation, but with a prayer of worship in chapter 3. From beginning to end, we overhear an intense conversation: the prophet wrestling with God over theodicy, the question of divine justice in a violent and unjust world.

This morning I want to explore Habakkuk’s complaint and God’s response, then see how Jesus addresses the same issue when the disciples cry, “Increase our faith!” Together, these readings give us a theology of faithful living when God’s ways don’t make sense.

Habakkuk lived in Judah’s final decades, a time of injustice and idolatry, with Babylon’s threat looming. His complaint isn’t about foreign enemies but about what he sees at home: violence, corruption, a legal system that protects the wicked. The law is paralysed. Justice never prevails.

And God seems to be doing nothing about it. “Why do you make me look at injustice? Why do you tolerate wrongdoing?”

This is the cry of someone who believes deeply in God’s justice and power. Habakkuk’s faith creates his crisis. If he didn’t believe God was just, he wouldn’t be troubled by injustice. If he didn’t believe God was powerful, he wouldn’t be frustrated by God’s apparent inaction.

Lament is a form of faith, not its opposite. You don’t cry “How long?” to a void. Habakkuk’s complaint assumes God is listening, God cares, and therefore God’s silence requires explanation. The very existence of this book in Scripture validates honest questioning as legitimate prayer. Habakkuk isn’t rebuked for his complaint. God takes his questions seriously and provides an answer, though not the answer Habakkuk expected.

After his complaint, Habakkuk doesn’t storm off in anger. He writes: “I will stand at my watchpost, and station myself on the tower; I will keep watch to see what he will say to me.”

This is the discipline of faithful expectation. Lament doesn’t mean abandoning one’s post. Habakkuk continues to watch, to wait, to expect that God will speak.

God’s response comes in two movements. First, concerning the vision’s timing:

“Write the vision; make it plain on tablets, so that a runner may read it. For there is still a vision for the appointed time… If it seems to tarry, wait for it; it will surely come.”

God tells Habakkuk to write the vision plainly because the community will need to remember it during difficult times. And God affirms: “There IS still a vision for the appointed time.” God has not abandoned history. Justice is coming. But it’s coming on God’s timetable, not ours.

This is one of Scripture’s hardest words: Wait. Be patient. Trust. The appointed time is coming, but we don’t control the schedule. When we see Manchester, Ukraine, Sudan, Gaza, or when we see corruption at home - we want God to act now. God says: there is an appointed time.

Second, God speaks the phrase that would echo through the ages:

“Look at the proud! Their spirit is not right in them, but the righteous live by their faith.” This single verse became one of the most influential in biblical theology. The Apostle Paul quotes it in Romans and Galatians, making it the foundation of his teaching about justification by faith. Centuries later, Martin Luther called it “the chief text of the whole Bible.”

In its original context, the verse sets up a stark contrast: the proud trust in their own power and schemes; the righteous trust in God. The Hebrew word translated “faith” is emunah, meaning both trust and faithfulness; loyal, covenant-keeping living. The righteous don’t just believe in God; they live faithfully, maintaining their trust through everything.

Notice what God does not say. God doesn’t say, “The righteous live by faith because they understand my plan” or “The righteous live by faith once I’ve explained everything.” Simply: “The righteous live by faith”- full stop.

So God’s answer to “How long?” is essentially: “As long as it takes. There is an appointed time. The vision will surely come. But meanwhile, here’s how you survive: by faith.”

Centuries later, the same struggle reappears when the disciples cry, “Lord, increase our faith!”

Jesus has just taught about radical forgiveness, forgiving someone seven times in one day. The apostles respond: “We don’t have enough faith for this. Give us more.”

This is deeply human. Faced with the kingdom’s demanding ethics - loving enemies, forgiving repeatedly, trusting God when violence strikes - we feel inadequate. We think, “I need more faith.”

But Jesus reframes the question: “If you had faith the size of a mustard seed, you could say to this mulberry tree, ‘Be uprooted and planted in the sea,’ and it would obey you.”

The mustard seed was the smallest of seeds. Jesus uses hyperbole to make his point: the issue isn’t the quantity of faith but its reality. Even the smallest faith, if it’s real, is sufficient because it connects us to God’s infinite power. Faith is not something we generate more of through willpower. It is God’s gift, a response to divine grace.

Then Jesus tells a parable: a servant works all day in the field, then prepares the master’s meal. The master doesn’t thank the servant for doing what was commanded. Jesus applies it: “When you have done all that you were ordered to do, say, ‘We are worthless slaves; we have done only what we ought to have done!’”

The parable breaks our illusion that faithfulness puts God in our debt. Our obedience is not leverage; it’s simply the fitting response to who God is.

This connects directly back to Habakkuk: “The righteous live by faith,” not “in order to obligate God” or “once we understand everything.” Just: “The righteous live by faith.”

So what does this mean for us?

It means we can bring our honest questions and frustrations to God. To continue to ask, “How long, O LORD?” about Manchester, about Ukraine, about Gaza and Sudan, about the moral weariness of our own public life. Habakkuk shows us that lament is legitimate prayer. To cry “How long?” isn’t weak faith, but faith that still turns toward the One who has already turned toward us in love.

It means trusting not in our capacity to believe, but in God’s faithfulness already revealed. We are not left to conjure trust out of thin air. The cross stands as the once-for-all assurance that God’s love endures every silence, every sorrow, every human cruelty. Faith is our response to that love - a trust that rests on what has already been given.

It means faithful service without demanding explanations. We pray for peace, support relief work, model reconciliation in our divided communities, refuse to let hatred win - not because we understand how it all fits together, but because it’s the appropriate response to who God is. The servant in Jesus’ parable didn’t need to comprehend the master’s entire strategy before ploughing the field. We don’t need to see the whole plan before we act faithfully.

And it requires mustard-seed faith maintained daily. Not extraordinary faith, just small, persistent trust that responds to love already proved. Perhaps your faith feels smaller than it once did, less a bonfire than a flickering candle. Yet even that is enough, because what matters is not the strength of our faith, but the strength of the One in whom we trust. The same Christ who stretched out arms on the cross holds us still; divine faithfulness makes our faith possible.

Notice too that God tells Habakkuk to write the vision for the community, not just for himself. We need each other in the life of faith.

When one person’s faith wavers, others hold the vision steady. When the waiting seems unbearable, the community reminds us of God’s appointed time. When violence strikes in Manchester, we stand

together. The church is meant to be a “Habakkuk community,” a people who bring honest lament, hold fast to God’s promises, and live by faith together whilst the vision tarries.

We also glimpse, beyond today’s reading, how Habakkuk’s faith is renewed. The book that began with a cry of protest ends with a song of praise. It is in worship

that his faith finds its footing again. Nothing in his circumstances has changed, but in turning toward God in praise, his lament is transformed. Worship does not erase the pain, but it reframes it.

It anchors faith not in outcomes but in the character of God, whose steadfast love has already been proved. So when we gather to pray, to sing, to share bread and wine, we too are shaped in that same

pattern: our faith fed by worship, our trust strengthened by grace.

Habakkuk’s book ends with extraordinary words:

“Though the fig tree does not bud and there are no grapes on the vines,

though the olive crop fails and the fields produce no food,

though there are no sheep in the pen and no cattle in the stalls,

yet I will rejoice in the LORD,

I will be joyful in God my Saviour.”

That is what it means to live by faith: not because we see the outcome, not because the headlines are good, not because we understand, but because God is faithful.

This is the faith Jesus calls us to: mustard-seed trust, service without bargaining, worship and perseverance while the vision tarries.

The vision has an appointed time. It will surely come. It will not prove false. Meanwhile, the righteous live by faith.

Thanks be to God.

Amen.

Trinity XVI, Sunday 5th October

by Fr Jack

Lamentations 1. 1-6

2 Timothy 1. 1-14

St Luke 17. 5-10

It is wonderful to hear the opening of St Paul’s second letter to St Timothy today as the epistle. And there in plain sight are these two wonderful women: Eunice and Lois. Mother and grandmother of St Timothy. St Paul knows them by name, he evidently knows their story. It is wonderful when the women of the Bible aren’t invisible-ised, as so often they have been.

I wonder what Lois and Eunice were like. How did they first hear the Gospel, so that they might bring up little Timothy in the faith? What made them follow Jesus? And their son and grandson, the bishop Timothy? What do we know about his life?

He was a bishop in the Early Church, as I say, (Presbyteros in the Greek of the New Testament sources - Presbyter, priest, elder. Just at the time that the Bishops and their deacons were beginning to become distinct from newer local junior Presbyteroi who ran the emerging network of smaller churches as the Christian community grew beyond one church per big city. In many ways, the same structure holds us today: Bishop Sarah down the road at the mother church, and lots of vicars vicariously in her place in the many local churches across the Diocese of London).

So we see already, apart from anything else, that St Timothy serves as a key example in our understanding of what happened to the Christian Church in the generation after the Apostles; as we settled into the patterns of life we now call, well, Christianity as we know it.

What else do we know about St Timothy? He travels with St Paul on his missionary journeys. And St Paul seems fond in other epistles of dispatching St Timothy here and there to support, encourage or guide. St Timothy is thought to have been a key editor of St Paul’s letters as they come to be in the New Testament too. A really important person in our Christian family story.

And here we pause to remember that some Pauline epistles are the oldest texts in the New Testament canon in terms of when they were written. For a long time after St Paul’s letters to the Thessalonians, Corinthians and Galatians, the Gospels were still shared orally, eventually being written down (we think) in the second half of the first century, 20, 30, 40 years after Jesus Resurrection and Ascension.

What about today’s epistle from Paul to Timothy? Scholars suggest that the letters to St Timothy are amongst the last New Testament texts to be written. So St Paul’s letters chronologically book end the New Testament, being amongst the first and last New Testament documents to be written. Corinthians (one of the earliest) is the fresh, chaotic, still dazzled by the glory of St Paul meeting Jesus on the Damascus Road. He’s asking, how are we to live? What is the basic DNA of living in the light of Jesus’ Resurrection and Ascension, writing as he was in the middle of the first century, just a few years after Jesus? Whilst today’s texts to St Timothy show us how the Church is maturing, maybe fifty years on, at the turn of the first into the second century, about 100 AD. The Jesus Movement is finding its way into a second generation of Christians.

And perhaps that’s why it poses questions like those that emerge from today’s epistle. Amongst them: how we live with hardship. Paul is writing about this today.

What tools of faith do we employ in times of hardship? What resources and relationships (internally, on earth, and in heaven) do we call on? What reservoirs of hope do we drawn from? St Paul lays out his and invites us to do as he does.

And this isn’t just a New Testament story. Deep in the Old Testament today, Lamentations records the ups and downs of history of ancient Israel. That history continues in Middle East - starkly present for us at the moment. But it’s not just the Mediterranean Middle East, the whole human family’s story is one of ups and downs, to put it mildly! Difficult times in life and faith are not strangers or imposters, they are simply part of reality.

So, perhaps the sensible thing to do is dig good roots for when (not if) trouble comes.

Perhaps that’s what we learn from today’s readings.

For example, I often reflect that Resurrection hope may not be very useful or easy to grasp for someone in the first tidal waves of grief. Instead, we need to lay those spiritual and theological foundations for when grief comes, and then we can call on on strong foundations, rather than be desperately trying to retro-fit them.

Likewise when we undergo suffering of any kind. Suffering is real and inevitable. Suffering can even be transformed by grace into great gifts, for ourselves and others. But you can’t say that to yourself or another very easily at the time of acute suffering! Instead, we have to lay the theological and spiritual foundations of life before, invest in a deep and prayerful personal relationship with God, so that He can hold us and gradually lead us on to hope when the time comes.

Returning to today’s readings: Saints Eunice and Lois laid foundations for St Timothy.

We do that for ourselves and others. How do we lay these foundations? In a million different ways: as we speak the Gospel normally and naturally at home, work, elsewhere. As we pray for people - sometimes we tell them we are praying for them, sometimes we don’t.

As we invite people to join us in church. A personal invitation from a fellow lay person is a thousand times more effective than a poster, or website or me and Revd Lucy wearing sandwich boards at Moorgate Station.

When I was first ordained I was nervous about inviting people to be Confirmed or Baptized. I didn’t want to make them feel awkward if they didn’t want to. I assumed they knew they could. But then more than once when I did happen to ask people said things like ‘I’ve waited 10 years to be asked’. And I wanted to say ‘its been in the notice sheet every week! You were asked in black and white. But that’s not the point.

More than once I have stood at a church door next to big poster that says: ’pleeeeease come to services’. And people ask, ‘am I allowed to come to morning prayer?’ What!? I’d love you to, that’s why I put all these posters up!

I have learnt and re-learnt that people are waiting to be invited. And they never mind being invited, even if they decline. And even the most hardened cynic, or member of another faith doesn’t mind being told - ‘I’ll pray for you’. Or ‘I prayed for you’.

So, we bring our mustard seeds, as in today’s gospel: we do our little bit.

We don’t claim to be anything other than servants of this much greater story (just as Jesus says today). Our faith may seem small, but the adventure in which we find ourselves is the greatest story ever told.

Jesus’ rather extravagant language today, as He is wont to do, calls us to be extravagant in return.

Extravagant in humility, yes, and extravagant in the joy and life we have been promised.

Extravagant in our hope, and knowledge that God’s Holy Spirit IS at work, even in little old me and little old you.

And if we pray and invite and serve, and rejoice and love, we are doing simply what we have been called and fed and sent to do. Nothing remarkable, just what we has been entrusted to us, for us to share.

We are servants who have been sent. And that is enough for us. Absolutely.

But, if we do it, we will find that it is not a burdensome duty or a painful labour, but an abundant and overflowing gift for us and for everyone around us. From Lois and Eunice, to Timothy and Paul, from them to us, and from us to the world.

Trinity XV, Sunday 28th September

by Fr Jack

Jeremiah 32. 1-3a, 6-15

1 Timothy 6. 6-19

St Luke 16. 19-31

‘I could have danced in front of you in a pink tutu’, says Abraham - well, sort of - today, ‘and you still wouldn’t have understood’.

Look again at this Gospel passage.

Jesus’ parable is necessarily black and white - that’s how it works as an illustration. It isn’t a fully worked out theology of how this life and the afterlife interact. It’s not pretending to be, it is one parable. But we can’t ignore its potency.

The judgement is real.

The responsibility is real.

The call on our lives is real.

That is the first thing to say.

The second is like, namely this: All those things are as real as God’s mercy, and God’s infinite love.

In philosophical terms, God is what is called a ‘simple being’. Not simple as in un-mysterious; that would be nonsense, obviously. But ‘simple’ as in, God does not have sides or moods or phases. God is complete, eternal and perfect. In classical theology, people like St Augustine (the great North African saintly bishop and theologian) want us to understand that God’s wrath is identical to God’s love. God’s judgment is God’s mercy. They are all one.

That should both pull us up sharp, and fill us with immense hope and gratitude.

So, back to Dives (which means the ‘rich man’ in Latin) and Lazarus

We are called not just to rely on God’s mercy for ourselves on that awe-filled day. But also to show it to others in the meantime! Our behaviour matters. Our choices are powerful.

When I meet God on the last day, face to face, when I see LOVE, pure Love Himself, face to face, I do not expect it to be an easy experience, but a glorious and wonderful one.

And I half expect Jesus to look like every beggar I have walked past in the street, every person I have neglected or harmed, gossiped about, our thought less of.

And certainly, all the securities and social mores I cling to in this life, won’t be of much use to me then.

St Paul the Apostle, writing to the Early Church Bishop St Timothy hits the nail on the head today:

17 As for those who in the present age are rich [as, by every measure across the human average in the world today, I certainly am], command them not to be haughty, or to set their hopes on the uncertainty of riches, but rather on God who richly provides us with everything for our enjoyment.

18 They are to do good, to be rich in good works, generous, and ready to share,

19 thus storing up for themselves the treasure of a good foundation for the future, so that they may take hold of the life that really is life.

Deep down we know this. So why do we live as if it weren’t the case in so many ways?

St Paul writes of contentment. We have been programmed very successfully to always want more. More choice. More stuff. More this, more that. More him or her. More immediacy, more so-called convenience. But all that is not really for our good, it is usually for the good of those who have so successfully trained us, like pets, to desire in the ways we do. This is especially so in the years since the end of WW2, and the rise of a mass-produced, advertising-based, global, consumer economy.

Admittedly, a situation that has been coupled with wonderful stability, peace, and prosperity, advances in health and education; so much good. But for all our progress, Dives and Lazarus persist.

There are clear links here with what popped out of last week’s readings, and that sermon is on the website, so I won’t preach it again.

Instead I want to notice questions of desire and trust leaping out of the readings given for today.

The Gospel and St Paul to St Timothy speak clearly and plainly. Take the Sunday sheet home, and as well as putting the notices in your diary or on the calendar in the kitchen, meditate on today’s readings across the week.

Including Jeremiah, to whom we will turn now.

The Jews in Jerusalem are under siege by the Babylonians in the tenth year of King Zedekiah. They are about to lose not only their capital city, their homes and businesses, but also the Temple itself. Their everything: the place of God on Earth, their connection and atonement.

And God, through the prophet, tells them nonetheless to buy land for houses and fields and vineyards where they are. It is an extraordinary promise, a radical hope. It will all go wrong, the exile really will be the ‘end of the world’ in so many ways for them; but build, build because God is faithful, and this will not be the end.

An amazing statement of where we put our trust. Not in riches or might, but in God’s faithfulness.

Trust, that is.

Not optimism, or ostriches with heads in the sand - but trust.

Not ignorance of our situation, but knowledge of the One with whom we are in this situation.

Not knowing that everything will be as we want it, but knowing that nothing can separate us from the love of God, (as St Paul writes to the Romans, and we hear at the start of the funeral service):

‘Neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, shall be able to separate us from the love of God, in Christ Jesus our Lord.’

And that is the only thing that truly matters. ‘That really is life’ as St Paul says today.

And this consideration of trust leads us briefly on to desire. Very clever people, who are very good at their jobs, have trained our desires for decades. Usually for their good, and not necessarily ours.

We are invited to do a little of this ourselves I response. To train our trust and our desire in healthy and good Gospel-shaped ways. Habits built on the wisdom of scripture, formed of the grace of the Sacraments, a trellis that supports us in prayerfully living the promises of our baptism, and the hope and trust that helps us to ‘take hold of the life that really is life’, as St Paul tells us today. Holy habits of Sacrament, Scripture and prayer. Holy belonging here in church and in other supportive relationships. There are so many ways to gently but firmly cultivate the habit of desiring and trusting into real life, not a million shiny plastic alternatives that are waved in front of us every day saying ‘desire me!’ Trust in me!’

‘Thus [as today’s epistle says] storing up for themselves [and those around us] the treasure of a good foundation for the future’.

What has arisen from today’s readings? Our choices matter. And God’s mercy and love are endless. God’s plan for us is good. Build well, and generously. Trust and desire in life-giving ways.

I’ll end with well-worn, but no less wonderful, words from St Augustine:

‘Great art Thou, O Lord, and greatly to be praised… we, being a part of Thy creation, desire to praise Thee, we, who bear about with us our mortality, the witness of our sin… yet … Thou movest us to delight in praising Thee; for Thou hast formed us for Thyself, and our hearts are restless till they find rest in Thee’

St Matthew’s Day, Sunday 21st September

by Fr Jack

Proverbs 3. 13-18

2 Corinthians 4. 1-6

St Matthew 9. 9-13

Reverend Lucy and I were speaking with someone this week, and we were asked how political our preaching is. It was amidst a conversation about the state of things today in politics and public life.

The lurch to the extreme in politics and society. 110,000 people marching in London last weekend. The decay of hitherto mainstream parties.

I answered that I don’t preach on politics. I don’t preach on the news. Almost never. With ten minutes in a Sunday morning sermon, the most urgent thing to be done is to dig around in the readings for today, and to see what God is saying to us.

And I said that I hope this gives people the theology which is the raw ingredients of their politics. I’m not going to preach a politics at you. Instead, I hope our preaching gives you the theological raw ingredients to do politics (and everything else) well.

Because our theology, our relationship with God, is not like a quirky old sports car we only take out on Sundays for a drive in the country, but the rest of the week is locked in the garage, not really useful for anything. No, our relationship with God, our theological way of being, is the ground of our whole being. It is who we are as we open our eyes in the morning, as we work, and love, and exist in relationship with friend and stranger. If we act as if God isn’t there, in any aspect of our lives, then we are living a lie.

I know how many of the people here this morning live from their faith beautifully - at work, home, the community, in so many ways. In this time of divisiveness and insecurity in public discourse, of people lurching to the extremes to find what feels like solid ground (even though it is nothing of the sort), we need to be renewed in our foundations and commitment.

We also need to be reminded that Jesus is always leading us on, and that we are never the finished article ourselves. Our views, our work, our way of being, cannot become too comfortable, or closed off by self-satisfaction, but must always be open to God’s Spirit and to growth.

It is to that Holy Spirit, under her name Wisdom, that the Book of Proverbs takes us this morning. More precious than jewels. Peace, prosperity: all these things are the gifts of wisdom.

It seems so often our society, here in the City and at large, has made wisdom (like faith, as I have said) a nice trinket, a toothless luxury, for some. But what really matters is the bottom line or power or measurable results. Wealth, brute strength and cunning seem to hold sway in so many things. Wisdom? Truth? How quaint.

Not so, says the ancient wisdom of Proverbs. What do we truly value?

How does the way we live together reveal what we truly value?

A wisdom revolution is what we’re being invited to live. Wisdom is gentle, wisdom knows what it does not know, and wisdom is also tenacious, brave, and far-sighted.

A moment ago we stood and chanted verses of Psalm 119. We prayed for God to fill our hearts and lives with His statutes, His wisdom, His ways. Pray the psalms at Morning and Evening Prayer here in St Giles’ and on your own using the free Church of England Daily Prayer app (we can show you how), and it will change your life. Live and breath these holy words that countless generations and Jesus Himself used as His prayer book, and together we will live this wisdom revolution.

But you can be forgiven for losing heart. Just as St Paul writes to the Church in Corinth today in the epistle. You can be forgiven for losing heart every time you see the news. It is real.

Douglas Adams, writes in his Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy:

‘For instance, on the planet Earth, man had always assumed that he was more intelligent than dolphins because he had achieved so much—the wheel, New York, wars and so on—whilst all the dolphins had ever done was muck about in the water having a good time. But conversely, the dolphins had always believed that they were far more intelligent than man—for precisely the same reasons.’

Basically, I’m saying, 'twas ever thus’. We speak of progress, and in many ways it's true. But humanity is still humanity.

So, if we aren’t to lurch into an extreme (necessarily half-blind) ideological corner, and if we aren’t to simply become nihilists who sit back with a negroni (as bitter as our hearts) and watch Rome and everything else burn, until we go up in flames with it…what are we to do?

Well, we have been here before. St Paul’s Epistles to the Corinthians, are just one example. He writes: we must refuse to practise cunning, or speak falsehoods, of God’s word or our own. We refuse to play the Devil’s game, even if others around us do - in personal and public life.

A revolution of wisdom. A revolution of truth and goodness. Look again, he writes: we commend ourselves of conscience and truthfulness, not cunning or strength or the game playing that so often fills the lives of those who appear to be on top. And it may seem, as St Paul writes, for a while that the Gospel is veiled: that evil is winning, that the good guys just get walked over and the bad guys win. And we start to ask, do we need to play dirty just to stay in the game? No.

Because we do not proclaim ourselves, we do not live our own lives only, but we are part of the living Body of Jesus Christ. It is His life we live. And He went to the Cross, because He refused to be anything other than who He truly was. And for precisely the same reason, death could not hold Him. The victory of darkness and evil is always, ultimately, temporary.

‘For it is God who says [writes St Paul today] ‘let light shine out of darkness’.

A revolution of wisdom, truth, and light. A Jesus revolution.

And it is that call that St Matthew hears today on his feast day. His own Gospel records this moment. A local guy who has sold his soul to the Roman occupier. Who extorts taxes and his own corrupt slice on top from the poor folk around him, presumably with thugs to protect him from retribution. The ‘Matthews’ of this world are alive and well, and Jesus calls him.

The Pharisees, for all their sincere devotion, had lurched into an extreme corner. They could make a good case, their reactionary but well thought-out YouTube channels and podcasts, would no doubt have impressed many were they here today. They were just tragically detached from the fundamental realities of who God is. In a bruised and battered world, they offered a compelling narrative of how to live, but for all that, they had become strangers to the grace and life of the Living God.

Jesus quotes Isaiah to them: ‘mercy not sacrifice’.

In a way sacrifice is much easier. Go to the Temple, buy an animal. It will cost you and you’ll feel the sting, but once you’ve done the deed, you’re done. You have fulfilled your obligation to God and humanity. Sorted.

But mercy? Mercy is much harder. Mercy is an ongoing relationship that makes space for mutual transformation, for forgiveness and thanksgiving. Mercy requires us to be open to the danger of being truly human together; sat round this table with Jesus, and with all those we find most difficult. There is nothing and no one outside God’s love, and therefore there is nothing and no one that we are not called into relationship with. A revolution (in these readings for St Matthew’s Day, and in this holy meal in which we partake) completely the opposite of a prevailing narrative that constantly downgrades our obligations to others, shrinks the human family into tribes, and hardens hearts; that divides to conquer, and exploits rather than serves.

But we here - we sinners - have been called to live (one moment at a time, one life at a time) a much more costly way. A Jesus revolution of wisdom, truth, and mercy.

Trinity XII, Holy Cross Sunday

by The Rev'd Lucy Newman Cleeve

Numbers 21.4–9

Philippians 2.6–11

John 3.13–17

Let me begin with a story.

Once upon a time, in a forest, there grew three little trees. Each had dreams about what they wanted to become when they grew up.

The first tree looked up at the stars twinkling through its branches and said, “I want to hold treasure! I want to be covered with gold and filled with precious stones. I’ll be the most beautiful treasure chest in the world!”

The second tree looked out at the small stream trickling by on its way to the ocean. “I want to be travelling mighty waters and carrying powerful kings! I’ll be the strongest ship in the world!”

The third tree looked down into the valley below where busy men and women worked in a bustling town.“I don’t want to leave the mountain top at all! I want to grow so tall that when people look at me, they’ll raise their eyes to heaven and think of God. I’ll be the tallest tree in the world!”

Years passed, and the three trees grew tall and strong. Then one day, three woodcutters climbed the mountain. The first tree was chosen and thought, “Now I shall be made into a beautiful treasure chest!” But instead, it was made into a feed box for animals - a simple manger.

The second tree rejoiced when the woodcutter said, “This tree is strong. This is perfect for me.” But instead of becoming a great ship, it was made into a small fishing boat.

The third tree’s heart sank when it was cut into heavy wooden beams and left in a lumberyard.

The first tree was disappointed. A manger? This wasn’t what it had dreamt of. The second tree was confused. A fishing boat? It had wanted to carry kings. The third tree felt forgotten, lying unused in a dusty yard.

But then, one starlit night, the first tree’s dreams came true in the most wonderful way. A young woman placed her newborn baby in the manger. Suddenly the tree realised it was holding the greatest treasure in the world - the Son of God.

Years later, the second tree’s dreams came true too. A group of friends climbed into the little boat, and one of them was the baby who had been born in the manger. When a storm arose and the friends were afraid, the man stood up and said, “Peace, be still!” Suddenly the tree knew it was carrying the King of Kings.

And the third tree? Years later, when that baby had grown to be a man, Roman soldiers made a cross from those beams. They forced the man to carry it up a hill and nailed him to it. The tree felt ugly and harsh and cruel. But on the third day, when the sun rose and the earth shook with joy, the tree knew that love had changed everything. Now, whenever people looked at that tree - the cross - they would think of God.

I’ve told you this story because today is Holy Cross Day, and it helps us understand what this feast is really about: how God takes what seems ordinary, even disappointing, and transforms it for glory.

Holy Cross Day takes us back to the year 326, when Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine, travelled to Jerusalem to seek the cross of Christ. According to tradition, excavations on Golgotha uncovered three crosses. To discern which one was the Cross of Christ, Helena prayed, and when one of the beams touched a dying woman, she was healed.

Nine years later, Constantine dedicated great churches on the sites of the crucifixion and resurrection. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was consecrated in Jerusalem on 14th September 335, and from then on Christians kept this day as a feast of the cross - not just to venerate the wood itself, but to celebrate the victory it represents: how God turns what seems like defeat into triumph.

Our first reading from Numbers tells us about another moment when God used physical matter as a means of grace. The Israelites were dying from serpent bites in the wilderness, having spoken against God and Moses in their discouragement. These were the same people God had just delivered from slavery in Egypt with mighty signs and wonders. They had walked through the Red Sea on dry ground. They had been fed with manna from heaven and given water from the rock. Yet when the journey got harder and the provisions seemed uncertain, they began to grumble against God and Moses.

But God’s response to the Israelites’ crisis wasn’t to abandon them - it was to provide healing. God instructed Moses to craft a bronze serpent and lift it up on a pole. Anyone bitten need only look upon the bronze serpent and they would be healed - a simple remedy requiring only obedient faith.

The very image of their affliction - a serpent - became their salvation when fashioned by God’s command and lifted up in faith. This might sound troubling at first - wasn’t this dangerously close to idolatry, worshipping a bronze snake? This is not what was happening at all. The bronze serpent didn’t heal because of any power in the metal itself. Rather, God chose to work through this physical matter, sanctifying it by command, transforming it into a means of grace. The healing came through obedient faith in God’s provision.

We see this pattern throughout Scripture: God working through physical, ordinary things to convey grace. Bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ. And today, as Stefania is baptised, water becomes, by God’s blessing, a means of grace through which she is cleansed from sin and reborn by the Holy Spirit.

But the ultimate example of God working through physical matter is the incarnation itself. Paul’s great hymn in Philippians - often called the “Kenosis Hymn” or “Carmen Christi” - reveals this deeper mystery. Christ, who existed in the very form of God, chose to empty himself, taking on human flesh, becoming human like us. God took on physical matter - a human body, human limitations, human experience - to reach us with grace. Christ humbled himself to the point of death - even death on a cross.

“Therefore,” Paul tells us, “God also highly exalted him.” The cross becomes the throne. The instrument of shame becomes the sign of victory. Every knee shall bow and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord.

Perhaps nowhere is this mystery clearer than in our Gospel reading. Jesus spoke these words to Nicodemus, who came to him by night, confused about what it meant to be born from above. In response, Jesus recalled that story in the wilderness: “Just as Moses lifted up the serpent, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.” Then came that magnificent declaration: “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son.”

In that lifting up we glimpse a great reversal. In Eden the serpent was the bringer of death; in the wilderness it became a sign of healing. In Eden, the tree became bound up with our fall; at Calvary, the tree of the cross becomes for us the place of life. As John of Damascus would later write: “The tree of life which was planted by God in Paradise prefigured this cross. For since death came by a tree, it was fitting that life and resurrection should be bestowed by a tree.”

And this is where all the threads of our readings are drawn together: The serpent lifted up, the hymn of Christ’s self-emptying, the son given in love – each of them pointing to the same mystery.

At the heart of it lie not mere belief as an idea – the word John uses for belief means to trust, to entrust oneself, to lean the whole weight of life upon Christ. This is the life that Stefania is brought into today – not simply a set of words to affirm, but a relationship of trust with the One who gave himself for her.

When Jesus spoke to Nicodemus, he made it clear: the Son was not sent into the world to condemn, but to save. The cross is not a sign of condemnation but of love poured out.

During the baptism ceremony, when the sign of the cross is traced on Stefania’s forehead, Christ claims her for his own. The cross - the sign of Christ’s victory over death - becomes the mark of her belonging to him, traced upon her life as a seal of protection and love. It will be her companion throughout life: reminding her that she belongs to the one lifted up for love of her; proclaiming that God’s grace reached her before she could ask for it; that love claimed her before she could understand it; that God’s victory covers her before she could earn it.

In these waters she is buried with Christ into his death, so that she may also rise with him to new life. Baptism is both gift and calling: gift, because it assures her that she already shares in Christ’s victory; calling, because it sets before her the pattern of his life. As she grows, the sign of the cross will call her into that pattern - a life of self-giving love, of obedient trust in God’s provision, of walking the way that leads through death into life.

Today we see again the paradox at the heart of our faith: what seems weak becomes strong, what seems foolish becomes wisdom, what looks like death becomes life. That paradox also runs through our own lives. There are times when we find ourselves in the wilderness – weary, doubtful or uncertain. Like Israel in the desert, we know how easily faith can falter. Yet the God who did not abandon his people then does not abandon us now. His grace is always greater than our frailty; when we are bitten by doubt, poisoned by cynicism or wounded by life, we can still look to the cross and live.

And perhaps we also recognise ourselves in those trees before they found their true purpose. Life has not turned out as we once hoped. Health may have diminished. Work or family life may look very different from our dreams. Our circumstances may feel more like a forgotten lumberyard than a palace throne room.

Yet God’s purposes are often fulfilled in ways we do not expect. The manger held the treasure of heaven. The fishing boat carried the King of Kings. The rough beams became the sign of salvation. In the same way, our ordinary lives, with all their disappointments and limitations, can be taken up by God for glory.

Look, then, at your own life - even its disappointing, ordinary parts - and ask how God might be at work in them.

On this Holy Cross Day, we lift our eyes to the cross - the place where suffering is turned into glory, and defeat into victory. And when the wilderness feels long and God seems distant, we are invited to look again to the one who was lifted up for love of us. Trust Him and Live. For the God who turned rough beams into the tree of life, who makes water the fountain of rebirth, who brings glory out of disappointment - this God has looked upon us with love, and made us alive forever.

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Trinity XII Sunday 7th September

by Fr Jack

Jeremiah 18. 1-11

St Paul’s Epistle to Philemon 1-21

St Luke 14. 25-33

Jeremiah says today that God will change His mind.

God doesn’t change His mind. God is God. Eternity, perfection, divinity - these things don’t change from lesser to more: they can’t. It’s sort of part of the deal.

What Jeremiah reflects here is how often we anthropomorphise God. God is a person, absolutely, but God isn’t an old man in the sky, a bit like us, just bigger, and older, and more in the sky. This could become a sermon about religious language, and what we can and can’t say about God. And I’d enjoy that very much, but that’s not what I want to explore so much this morning.

What I want to acknowledge as we start is that Jeremiah’s words say as much about our human ability to relate to God, who is always beyond our comprehension, as they do about God.

Look at the way Jeremiah speaks about sin. We humans drift off, away from God’s loving plan for us, and things go wrong. And should we be surprised!? And yet, somehow, we always are. We talk of teaching children through consequences. And these are natural consequences. Jeremiah speaks of it like thunder bolts from God in punishment, of course he does. But isn’t it as much revealing the natural consequences of sin? If we go off course by idolising wealth, power, violence, some aspect of our identity or anything else, guess what, we are not being who God made us to be, and things go wrong. Should we be surprised?

I know I’ve mentioned this before. We poison this beautiful world God has given us, we speak and echo inhumanity, and we are surprised things go wrong?

Sin has natural consequences.

So what are we to do?

Well, now we turn to St Paul’s Letter to Philemon. The Apostle is writing to a part of the Early Church, and he writes of love.

St Paul wants us to see that love is our DNA. Crucially, he says, love, not commands.

Rules and punishments will alter people’s behaviour. They will sometimes prevent the worst of things happening, but they can never achieve the best of things.

You can stop someone beating up an old lady and nicking her purse with the threat of punishment, but only human flourishing and mutual love can inspire someone to truly love their neighbour, and see Christ in them. The answer (to sin and its myriad consequences) in Jeremiah, in St Paul and in most of all in Jesus, is not regulation but love.

The Kingdom of God cannot be got to through laws and policing and courts.

And this is not ‘airy fairy’ or ‘pie in the sky’ - here and now we are living into the Kingdom.

We have been baptized into it, and it and it alone will last forever. The answer to heartache and division and fear and violence, is this Kingdom of love, this Kingdom of God. Nothing else will do.

We will taste a fore-taste of it in a few moments when we receive the Body and Blood of the One who rose from the dead and ascended into heaven, into His Kingdom, so that we might follow Him there.

And every day of our lives, we are a people gathered, fed, and sent to be people in whom the world can see Jesus, and smell and taste and know His Kingdom. Even in this world so battered by sin and our broken responses to it. We are baptized and gathered and fed and sent, to be that Kingdom at work, at home, in communities, with friend and enemy, loved one and stranger.

In some ways our faith is ever-so complicated and mysterious, and requires us all to have 12 PhDs in theology to get anywhere. But then again, our faith is also remarkably straightforward.

And here we get to the Gospel given for today.

One of those passages that Jesus quite clearly said to provoke people, and it still does today. These words are twenty centuries old, and as sharp as ever.

‘Hate’ - famously a strong word. And remember Jesus is speaking in a society where familial ties are exceptionally strong. Who you marry, where you live, what you do all day - these were largely not matters of choice. They were determined by your situation and, alongside that, your family or other local hierarchies. So for Jesus to undo all those powerful structures must have been astounding. And then He goes further - you must even hate your own life!?

And perhaps we’re too busy being shocked by this to see that Jesus, in a classically rhetorical stroke of His rabbi’s tongue has not hurt us, but freed us. He has cut us from stifling bonds of approval, of acceptability, of ambition, and comfort, of what others think, of what we think we need to be happy or safe or complete. All of it is cut away in this fiery turn of phrase.

And we are invited, instead, to be nothing other than a disciple of Jesus Christ.

For some reason I found myself this week (before I’d even read the readings for today) thinking about what it would be like to ask the people around me: ‘what are you?’. Its a rude and pompous question when I ask it, so I don’t think I shall. But, what are you?

What’s the first thing that comes into your head?

I decided in my idle musings, that I wouldn’t ask, ‘who are you?’, because then you might just answer with your name too instinctively. But, ‘what are you?’.

Is the first thing that comes into your mind a job title, or a status like ‘a child’ or ‘retired’? Or is it an identity marker, something you’ve had from birth, or one you’ve picked up later?

Jesus today is cutting away all these things, not because He wants to harm us, but because He wants to free us.

I guess it all comes down to this (and thinking about those two analogies Jesus uses of having worked out what you need to have before you start - the tower builder or the king and his army): by needing to have less, we find that we actually have all that we need.

If all we need to be is a child of God our Father, and a disciple of Jesus Christ, we find that we need nothing more. That we are nothing more. Is that what Jesus means to be free by hating your life? TS Eliot, in Little Gidding, the climax to his magnificent spiritual poems the Four Quartets, leads into a quotation of Julian of Norwich calling it:

‘A condition of complete simplicity (Costing not less than everything) And all shall be well and All manner of thing shall be well.’

If, as we go through life as followers of Jesus, as we live more and more into His Kingdom, if we do acquire more things (possessions, familial relations and the rest of it) we discover that our relationship with them is now quite different. They no longer possess us, but become blessings we desire to hold lightly and to give away.

So - looping back to where we began - Jesus is not commanding us to do this, He is simply inviting us to do this, because He loves you. He isn’t recruiting followers by threats or good sales to boost His own profits. Remember, human beings might act like that, and we so easily act as if God was like us. But, God is God. God’s desire for us is that of a lover, who loves us and knows us more than we could ever love or know ourselves or each other.

Jesus is not threatening us. He is simply explaining that living worshipping our fantasies about ourselves, our possessions, our social norms… answering the question ‘what are you?’ with something other than ‘I am a child of God, a follower of Jesus Christ’ will never bring us to be our true selves.

Just as St Paul is trying to tell us, He is not commanding us into His Kingdom, He is loving us into it. And only this love, this Kingdom, can answer the world’s sorry state, all those natural consequences to sin that Jeremiah laments.

I’m not going to tell you how to put this into practice. We all have different false gods that need disposing of, and it’s always a constant process of renewal, of liberation. But I am going to suggest that we all ask for God’s help in the silence after Holy Communion and in your private prayers this week. Begin again today and every day of our lives to be free for the Kingdom, because that alone will last forever.

Feast of Saint Bartholomew 24th August 2025

by Westcott House Ordinand Sarah Fagg

May I speak in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, Amen

Today the church celebrates Saint Bartholomew also known as Nathaniel. He is one of the 12 Apostles. He is most well known for his missionary work. It is said that he suffered a rather gruesome martyrdom, possibly by being flayed alive and then crucified or burned alive.

Nathaniel is known for acclaiming that Jesus “is the son of God, the King of Israel”. Which can be found in John’s Gospel. Perhaps one of the first disciples to go from doubt when he says to Philip “can anything good come from Nazareth”to full acceptance of who Jesus is.

Saint Bartholomew’s openness about his doubt leads him to encounter God. Even when he was doubtful at first his inquisitive step towards Jesus was enough and the presence of the Son of God was made known to him. It seems God encourages honesty about our doubts because then they can be transformed into belief.

In our passages today, they seem to be connected in calling us to have faith. To reflect on what might be possible when we have faith in God. That we can obtain eyes that see, ears that hear. That we can be confident in a God that heals. That through God’s grace we are called to be transformed into holiness leading us to serve and care for one another.

In the Isaiah passage it talks about people who have eyes, but are blind, people who have ears but are unable to hear. I don’t know about people here today but when I read these passages and knowing Isaiah was prophesying to people who had strayed away from their faithfulness to God, I often say an internal prayer, Lord please let me hear you and please let me see you!

It leads to questions what could it mean to have been given these gifts from God eyes and ears?What do we miss if we don’t use them to see and hear the grace God wants to show us.

We are called to worship God, so what could it look like to first we use our eyes and ears to praise God and build a relationship with Him? To be faithful in seeking out what God wants to show us.

The passage goes on to explain that there is no other Saviour but God, so we ought to use our senses to connect to Him. There may be times especially when perhaps we have lost faithfulness that our senses are detached from God. We may be tempted to turn towards false idols.

It is fair to say that perhaps when we do not see and hear the signs we would hope for from God we may well begin to look elsewhere. But my encouragement from the Isaiah passage is to keep faithful and keep looking towards God.Even when it is hard and we want to avoid God, let’s try to continually turn our gaze towards God.

In our passage from Acts, we have beautiful examples of faith within the early church. People bringing out those who are ill knowing that the Holy Spirit has been gifted to the church giving grace to heal. What could it have felt like to be a member of the early church? Or even to be an Apostle? It must have felt incredible to be able to heal and demonstrate God’s love for people in a physical way.

It would have taken a strong faith - faith by the Apostles that the Holy Spirit would guide them inproviding healing. Also the faith of the people of the towns who were gathering people and believed that they would be healed. The fruits of this faith was that the disciples grew in number and the gospel was able to be shared with more people. Bringing hope to more people.

May we have faith that we can seek the Holy Spirit to guide us in providing healing to those we meet. Also that God will use us to bring more people into a relationship with Him.

In our gospel passage it shows the usual topsy turvy world of the gospel. The person who is the youngest is the wisest, the person who we would expect to be served is the one who serves.

It is interesting to consider what it means to be like a child and why Jesus says this is important.This is also not the first time Jesus mentions being like a children in order to go into the kingdom of heaven.

I don’t think Jesus is advocating that we all become people who believe anything that we are told. More that we have a broader faith because we will all have at times experienced the wonders and miracles of God. This can also provide comfort that even when things are not so good or perhaps God seems distant we can have faith and hope because we have seen the miracles and mysteries of God.

The Gospel passage provides a challenge for us today, in that it encourages us to be generous with our time and to serve one another. This can at times push us into feeling guilty or perhaps like we do not do enough, but I would like to provide encouragement that I have witnessed beautiful love and service in the short time I have been in this wonderful community. It has been a blessing to be with you all, the welcome I have received has been truly inspiring. I am almost certain this place and community honours God.

The Gospel also seems to be broken down into two sections. What we can do now whilst living on earth and what may happen when we enter the kingdom.

The passage moves us towards a heavenly banquet where in God’s kingdom we will be invited to eat, drink and sit at the table with God. We are fortunate that we receive a foretaste of this at the Eucharist. Today when we approach the altar we are united with heaven, how amazing is that, we are invited to sit and eat with God in his Kingdom. What an incredible uncomprehensible gift we have been given.

We can have faith that through the Holy Spirit, Christ is made truly present to us in the bread and wine. The gift which Christ left us which we need humility and faith to try to comprehend the mystery, but also that it transforms us to go out into the world and serve our community.

It may not always be clear where God is and how His goodness is poured out into the world. But on this Feast of Saint Bartholomew, he provides an example that even a grain of curiosity and faith is enough to lead us to God which can direct us to have eyes that see beyond our initial doubts.

So as we journey into the week ahead I would like to encourage us to put our faith in God, even when He may seem distant. Let us be bold like Saint Bartholomew to follow God even when we are not certain, and have comfort that God will work within us and through us, even when we have doubt. That through faithfulness, we can build a deeper rooted relationship with God, knowing that we can put our trust in Him. Amen

Ninth Sunday after Trinity, by Edward Smyth of the Prison Reform Trust

17th August 2025

Isaiah 5.1-7, Hebrews 11.29-12.2, St Luke 22.49-56

‘And he looked for justice, but saw bloodshed; for righteousness but heard cries of distress.’

I ought, really, to begin this slot as a guest preacher by thanking Fr Jack for the invitation to this splendid church which is, as it happens, mere moments from the office of the Prison Reform Trust where I am the Head of Development.

And indeed I fully intended to do so...until I looked at today’s readings and realised that Fr Jack had, in fact, quite royally done me over.

Because this is a bracing set of readings for a quiet summer Sunday in central London. The compilers of the lectionary, I can only assume, feared that our concentration may have lapsed in the heat – that we had perhaps become complacent...yep, God is Love, feed the hungry, clothe the naked, love your neighbour – got it. What time’s lunch?

I confess, I quite like my Jesus Victorian. Meek and mild; no crying he makes; cherubic and squidgy. ‘I have come to bring fire on the earth, and how I wish it were already kindled. Do you think I came to bring peace on earth? No, I tell you, but division.’

Ah.

About three months ago I travelled – for the first time – to HMP Swaleside, a high-security men’s prison on the Isle of Sheppey. Swaleside is a troubled place – what some in my world would call a ‘proper prison,’ holding mostly prisoners serving very long sentences for some very unpleasant crimes – and it is a prison which has chronic issues with drugs being delivered by drone, violence, and genuinely shocking levels of self-harm and suicide.

I am not a Londoner by upbringing, and I am therefore not one of those people for whom the world outside Zone 1 is a terrifying place, and comes to an end entirely as one reaches the M25. But the trip to Swaleside was striking. I often describe prisons as society’s ‘dark places,’ – places where we send people at least in part to forget about them – but I have rarely had that sense of a division from society so starkly demonstrated. There was something genuinely disconcerting about that trip: crossing the Kingsferry Bridge onto the Isle of Sheppey, rain beating down on the windscreen; following the map away from civilisation down roads of increasingly loneliness before, finally, turning into a gloomy lane which ran a mile towards the three forbidding prisons of the ‘Sheppey Cluster.’ Other than a few wind turbines there was nothing else so far as the eye could see. As I arrived a bus disgorged its passengers. There are very few sadder sights than arriving at a prison as a ‘family visit’ is about to take place: the vision of a handful of – mainly – women with small children inadequately wrapped up against the horizontal rain was a sobering one.

This kind of ‘out of town’ prison is now the norm. There are obvious economic and practical arguments in favour of putting prisons in the middle of nowhere; but more fundamentally this is a direct consequence of a shift in society’s philosophy of punishment which we can date roughly to the eighteenth century. It is at that point, as any of you who know your Foucault will – gorily – remember, that the state’s response to criminal behaviour began to shift from the body (deterrence) to the mind (rehabilitation). Before that – indeed for many thousands of years – prison was where you went to await your punishment (execution, flogging, deportation etc); after this prison was your punishment. And so with more and more people spending longer and longer in prison as an end in itself, more and larger prisons were required...and today we find ourselves with massive warehouse-style prisons – such as the new HMP Millsike in Yorkshire, the opening of which I attended in March – built on land sold to the Government by now extremely wealthy pig farmers. His attendance at the ribbon-cutting at Millsike was an odd sight indeed.

A common response to the kind of things I have just said – about the terrible conditions at HMP Swaleside and about the shift towards out-of-town prisons – is ‘Who cares?’ – and I don’t know, perhaps there are people here this morning thinking the same thing. Prisoners are hardly a sympathetic group, an observation borne out by successive governments’ handling of issues of criminal justice: anything other than ‘more punitive’ and ‘more prisons’ is a guaranteed vote-loser.

A vicar friend of mine once told me that the moment a preacher says ‘as T.S. Eliot wrote...’ he immediately switches off and starts thinking about the football. In my line of work the equivalent is ‘as Churchill once said.’ As Churchill once said... well...actually, he didn’t say what usually comes next, which tends to be that ‘you can judge a society by how it treats its prisoners.’ That was Dostoyevsky. And it’s a decent sentiment in my view, but it’s not as good as what Churchill actually said which I am going to recount, with apologies both for its length, and for the inevitable moment I slip into a Jim Hacker-style impression – surprisingly difficult not to do.

The mood and temper of the public in regard to the treatment of crime and criminals is one of the most unfailing tests of the civilisation of any country. A calm and dispassionate recognition of the rights of the accused against the state and even of convicted criminals against the state, a constant heart-searching by all charged with the duty of punishment, a desire and eagerness to rehabilitate in the world of industry of all those who have paid their dues in the hard coinage of punishment, tireless efforts towards the discovery of curative and regenerating processes and an unfaltering faith that there is a treasure, if only you can find it in the heart of every person –

these are the symbols which in the treatment of crime and criminals mark and measure the stored up strength of a nation, and are the sign and proof of the living virtue in it.

There’s a reason I began this sermon with a line from today’s Epistle. Because if you go into a contemporary British prison looking for justice, you will all too often find bloodshed instead. And if you go into a contemporary British prison looking for righteousness you will all too often – always, in fact – hear the cries of distress instead. Our prisons are a disgrace, and I maintain this:

- It is perfectly possible to believe that prison is an appropriate expression of society’s censure of an act and be a Christian

- It is perfectly possible to believe that there are some people who quite simply cannot ever be released from prison and be a Christian

- It is perfectly possible to believe that one of the functions of prison is to deter others from behaving in a similar way and be a Christian

- But it is not possible to be a Christian and to think that prison should be a place where hope is extinguished, where people are and should be harmed and, all too often by their own hand and by the hands of others, killed, and where rehabilitation is all too often not even attempted.

And that is the reality of our prisons today; and that is why we should care.

There are plenty of people in my world who advocate for the abolition of prisons. I am not one of them; and nor is my employer. Plenty of people in prison believe the same thing, incidentally: that their sentence is entirely justified and, in fact, that serving it is part of their process of atonement. I think I can take as read that, as Christians, we cannot condone a blanket throw-away-the-key approach. As such, most people will be released from prison one day and it is in society’s interest to ensure that they emerge better, not worse, than they went in. But more than that, it is simply the right thing to do. To do otherwise is to scapegoat; to condemn; to hate the sinner and not the sin; to refuse to see that treasure in the heart of every man and women, if only we can find it. It is the state’s job to punish. It is our job to look for the treasure. Those two things can happen at once and they should happen at once. All too often we won’t find it. But to look is our calling. To allow prisoners’ appropriate and justified division from society to serve as an excuse not to look – not to care? Then we deny that calling.

The end of our Gospel reading today has Christ admonishing the crowd as ‘hypocrites!’ for being able to interpret signs of the weather, but failing to interpret – or, rather, choosing not to interpret – the signs of the times. Too often we fall into the trap of allowing our interpretation of God’s call on us and our lives to ossify: we find an interpretation we’re happy with, and we stick to it, living our lives comfortable under the misapprehension that we’re doing what’s asked of us. But God’s call is a living thing, and it is whispered into our ears all our lives long. God will sometimes ask new, difficult things of us. Our views on people in prison and our attitude towards them I think similarly ossify. But that Epistle passage is for me – and perhaps, I hope, for you – a whisper worth listening to and, crucially, responding to.

And he looked for justice, but saw bloodshed;

For righteousness, but heard cries of distress.

Amen.

Installation Service of the Master Barber

14th August 2025

By Fr Jack

The three hymns that the Master and Mistress have chosen for us to sing tonight are from their wedding. It is lovely to sing them with you now, Master and Mistress, to rejoice in your love, but also because it shows just what magnificent hymns these are. Hymns, truly, for all occasions.

Look again at them… (Praise my soul the king of heaven. Lord of all hopefulness. All my hope on God is founded)

There is not a day in anyone’s life that is not expressed and enriched, cleansed and calibrated by words and music like these. Sing more hymns!

On days of joy, sadness, weariness, worry, boredom or nothing much. Hymns like these are treasures that speak into every part of life.

And the reason I say all that, is because we Barbers share a similar God-given vocation. Like these hymns, we are called to be evergreen, to speak blessing into the realities of life, and to be stewards and sharers of God-given treasures. Let me explain.

Firstly.

Another year turns, another Master is installed. It is the same as it has always been, and yet tradition (at least as the Christian tradition bids us understand it) is alive. Tradition is alive with lives and stories of the people who have received it, who live it, and who pass it on. This is the story of the Church. This is the story of the Livery.

This is the human story. We here proclaim that we are not self-creating independent units, but treasuries of relationship and connectedness. People and God together.

Secondly.

As a Company, we bring the hodge-podge mixture of our lives (all those joys, sadnesses, weariness, worries, boredom or nothing much-es) and we quite literally embody together that reality, that mixture. The very fabric of our lives (and through us the whole human family) is hallowed by being brought through us now to church in prayer and worship, and hallowed too in the fellowship of our common table. We are guests of the Lord at dinner, as well as in church.

Thirdly.

We also see our hymn-like vocation in what we come together to do. The Court met this afternoon in an act of trust. To entrust the life and story of our Company to a new Master and set of Wardens. We come to Church now to entrust the Master, Wardens, our Company, and the whole human family to God: recognising quite deliberately that the really important things of this life are not ours to possess. The wisdom, skill, love and imagination we need (in professional life, at home and in the Company) are not, honestly, ours. They are gifts, from God, just as St Paul tells us in the third reading this evening.

The Master has spent many years using his gifts to treasure life, specifically the lives of the children he has served as a paediatric oncologist. Our company also expresses its vocation by celebrating you Master and your work. You have done just as Jesus says in tonight’s second reading, by treasuring the little ones the Lord loves, and bids us all become like.

Let me draw these threads together and finish. In the first reading, Jesus speaks the beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount. These words, like those of our hymns are evergreen. If you were to speak them every day of your life they would never grow stale and never be out of place. They honour the messy reality of the human experience, and they speak of a courageous hope. Not a pipe dream, not naivety or fairy stories, but courageous hope. They speak into the story that is our story, of people and God - through love and service, worship and prayer, community and every gift that God gives us - living more and more towards the Kingdom of God, here and now, and in the hereafter.